Massage can facilitate soft tissue expansion

Weicheng Gao, Shaolin Ma, Xianglin Dong, Tao Qin, Xing Qiao and Quan Fang

Medical Hypotheses

Volume 76, Issue 1, January 2011, Pages 148-149

Soft tissue expansion is a helpful technique in reconstructive plastic surgery. Unfortunately, tissue expansion still needs to be improved. Tissue expansion is one of the most useful techniques in plastic surgery. However, it takes a long time to obtain it. Some investigators have reported several agents that speed up tissue expansion, but none of these agents has been used in routine clinical practice. Tissue expansion is a mechanical process that increases the surface area of local tissue available for reconstructive procedures. Living tissue responds to the application of mechanical force. Continual inflation of an expander increases the overlying tissue by inducing an increase in mitosis and stealing next tissue.

Various agents and topical creams have been found to enhance tissue expansion by different methods. After reviewing the article around the world, we haven’t found any paper that tell the correlation between massage and soft tissue expansion. In our current article we evaluated the effect of comfortable tissue expansion using topical massage application.

Massage is a comprehensive intervention involving a range of techniques to manipulate the soft tissues around the soft tissue expander. For patients who is experiencing soft tissue expansion with depression, anxiety, or other secondary problem, massage may be a useful adjuct to medical treatment. According to our clinical experience, not only massage is a relatively safe form of treatment with high levels of patient satisfaction for pain reduction and simultaneously, anxiety disappear evidently, but also can speed up tissue expansion.

The use of massage for pain and anxiety reduction and, warrants further research to investigate efficacy, effectiveness, mechanism of action, patients’ perceptions, and cost effectiveness for a variety of plastic and reconstructive conditions. Nurses, physical therapists, and massage therapists commonly practice a technique using hand strokes from the distal portion of the limb to the proximal in a circular pattern14; this helps to redirect fluid from one area of the body to another. Furthermore, effleurage, light manual rubbing, a classical type of massage, retrograde self-massage, and gentle, rhythmic stroking may result in a mild pressure gradient, assisting in removing edema from the affected part of the expanding soft tissue; these techniques may be administered by a properly trained therapist, nurse, or by the patient’s significant other following adequate instructions and proper demonstrations. In addition to the physiological benefits of expanding soft tissue massage by a significant other, patients experienced a range of emotional and mental benefits. Patients reported being comfortable and relaxed during massage, especially during the whole process. Bredin described the touch of a massage as a method of communication that expresses the other person’s willingness to tolerate and accept the woman after her disfiguring surgery.

Our experience shows that massage can improve the rate of tissue expansion by local massage application combined with eye ointment cream application. This means that application of topical massage combined with eye ointment cream to facilitate tissue expansion is simple and effective. In summarize, the effect of massage on soft tissue expansion is probably as follows: (1) reduce the pain in the period of inflation; (2) improve anxiety; (3) preventing or improving capsular contracture around the expander ; (4) increasing circulation or blood flow; (5) as a method of communication between plastic surgeon and the patients.

From Journal of Bodywork & Movement Therapies

Vladimir Janda, MD, DSc (1923–2002) influenced generations of practitioners spanning many disciplines. This evidence-based book is written by three physical therapists, all of whom worked with Janda. It emphasizes various assessment and treatment procedures based on the existence of muscle imbalance – the combination of abnormal muscle inhibition (“weakness”) and hypertonic muscles (tightness). This would make a useful addition to every clinician’s library – especially physical therapists, chiropractors, osteopaths and all those using hands-on therapies.

Vladimir Janda, MD, DSc (1923–2002) influenced generations of practitioners spanning many disciplines. This evidence-based book is written by three physical therapists, all of whom worked with Janda. It emphasizes various assessment and treatment procedures based on the existence of muscle imbalance – the combination of abnormal muscle inhibition (“weakness”) and hypertonic muscles (tightness). This would make a useful addition to every clinician’s library – especially physical therapists, chiropractors, osteopaths and all those using hands-on therapies.

The book is divided into four parts:

- – The Scientific Basis of Muscle Imbalance includes chapters on the structural and functional approaches to muscle imbalance, and the “pathomechanics” of pain.

- – Functional Evaluation of Muscle Imbalance discusses posture, gait, muscle length testing and soft tissue assessment.

- – Treatment of Muscle Imbalance Syndromes describes the restoration of muscle balance and sensorimotor training.

- – Clinical Syndromes presents four common areas of musculoskeletal pain disorders: cervical, upper extremity, lumbar and lower extremity.

Like many pioneers, Janda’s terminology and ideas evolved apart from the traditional clinical sciences. The author’s state: “There are several schools of thought regarding muscle imbalance. Each approach uses a different paradigm as its basis. Vladimir Janda’s paradigm was based on his background as a neurologist and physiotherapist.”

The Janda Approach provides more than an introduction of his material for practitioners and students. In the preface the author’s state: “We wanted to write a text that both preserves and supports Janda’s teaching. This book is only a tool for everyday practitioners; it is not meant to address all chronic pain syndromes or even all muscle imbalance syndromes. Instead, we wanted to provide practical, relevant, and evidence-based information arranged into a systematic approach that could be implemented immediately and used along with other clinical techniques.”

An important concept presented well is the interplay between injuries and muscle imbalance. Janda’s “muscle imbalance continuum” describes tissue damage, pain and altered gait as potential causes of imbalance, while emphasizing that the reverse can also exist.

The book’s wide range of topics associated with neuromuscular function is as impressive as the therapeutic options offered – from acupuncture and trigger point therapy to the works of Florence and Henry Kendall, and George Goodheart. All the topics are well researched with 40 pages of references.

Janda’s view of muscle imbalance is presented well – the combination of tight/short muscles and weak ones, mediated by the central nervous system with important stimuli from the peripheral nervous system (in particular, proprioception from joints). While the book references Sherrington, Janda often deviated in his approach by treating the tightness as the primary muscle problem rather than the weakness.

The book’s side-by-side comparison is made between Janda’s clinical approach to muscle imbalance and that of physical therapist Dr. Shirley Sahrmann. However, to help address the common debate among clinicians regarding which side of muscle imbalance is primary, it might have been useful to also present the different perspectives adopted by physical therapist Diane Damiano or George Goodheart DC whose clinical work focused mainly on muscle weakness. The interpretation of Sherrington’s law of reciprocal inhibition appears to be the difference. The Janda Approach does recommend using muscle testing in certain cases, and suggests, at times, treating the weakness side of muscle imbalance.

The Janda Approach describes a full spectrum of muscle imbalance – from relatively common problems associated with aches and pains, including chronic low back syndrome, to the more serious mechanical distortions in brain and spinal cord injured patients. An important tenet is worded well by the authors: “[Janda] based his approach on his observations that patients with chronic low back pain exhibit the same patterns of muscle tightness and weakness that patients with upper motor neuron lesions such as cerebral palsy exhibit, albeit to a much smaller degree.” Janda believed that 80% of patient’s with low back pain could be shown to have minimal brain dysfunction.

In our symptom-oriented healthcare world, it was refreshing to read Janda’s philosophy that the source of pain is rarely the cause. The book dedicates a chapter to this concept of interactions between the skeleton, muscles and nervous system, and the process of cause and effect. While the authors describe Janda’s many clinical models, clinicians are well aware that patients typically deviate from these patterns, creating their own unique neuromuscular patterns.

Like many chapters, the one on posture, balance and gait is excellent. However, despite writing his first book on muscle testing, The Janda Approach describes only a few manual muscle tests, instead relying more on posture, gait, muscle length assessment and basic movement patterns to evaluate muscle imbalance.

Because Janda felt that manual therapy was not sufficient by itself to successfully treat the neuromuscular system, the authors discuss his sensorimotor training as an important aspect of patient care. Rather than traditional strength training, Janda used sensorimotor training to promote whole-body neuromuscular activity with emphasis on incorporating certain areas of the brain. These include gently increasing proprioception from the sole of the foot, deep cervical musculature and the sacroiliac joint, as well as vestibular balance training. These physical activities help activate/retrain the motor system, improve postural control and optimize gait.

The last part of the book contains four chapters, each representing a common clinical syndrome by region: cervical, upper extremity, lumbar and lower extremity. Case histories offer good examples, but they don’t replace an effective assessment and the potential for a wide variety of therapeutic options – many of these are offered by The Janda Approach.

Despite this reviewer’s many years of study of Janda’s work, this book provided much new information and ideas, largely because the authors present the material so well.

BACKGROUND: Pain is a global public health problem affecting the lives of large numbers of patients and their families. Touch therapies (Healing Touch (HT), Therapeutic Touch (TT) and Reiki) have been found to relieve pain, but some reviews have suggested there is insufficient evidence to support their use.

OBJECTIVES: To evaluate the effectiveness of touch therapies (including HT, TT, and Reiki) on relieving both acute and chronic pain; to determine any adverse effect of touch therapies.

SEARCH STRATEGY: Various electronic databases, including The Cochrane Library, MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, AMED and others from their inception to June 2008 were searched. Reference lists and bibliographies of relevant articles and organizations were checked. Experts in touch therapies were contacted. SELECTION CRITERIA: Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) or Controlled Clinical Trials (CCTs) evaluating the effect of touch on any type of pain were included. Similarly, only studies using a sham placebo or a ‘no treatment’ control was included.

DATA COLLECTION AND ANALYSIS: Data was extracted and quality assessment was conducted by two independent review authors. The mean pain intensity for completing all treatment sessions was extracted. Pain intensity from different pain measurement scales were standardized into a single scale. Comparisons between the effects of treatment groups and that of control groups were made.

MAIN RESULTS: Twenty four studies involving 1153 participants met the inclusion criteria. There were five, sixteen and three studies on HT, TT and Reiki respectively. Participants exposed to touch had on average of 0.83 units (on a 0 to ten scale) lower pain intensity than unexposed participants (95% Confidence Interval: -1.16 to -0.50). Results of trials conducted by more experienced practitioners appeared to yield greater effects in pain reduction. It is also apparent that these trials yielding greater effects were from the Reiki studies. Whether more experienced practitioners or certain types of touch therapy brought better pain reduction should be further investigated. Two of the five studies evaluating analgesic usage supported the claim that touch therapies minimized analgesic usage. The placebo effect was also explored. No statistically significant (P = 0.29) placebo effect was identified.

AUTHORS’ CONCLUSIONS: Touch therapies may have a modest effect in pain relief. More studies on HT and Reiki in relieving pain are needed. More studies including children are also required to evaluate the effect of touch on children.

Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (4), pp. CD006535

Pelvic floor exercises have long been recommended for women – now researchers say they could help men too. The exercises were found to help men with erectile dysfunction as much as taking in Viagra.

The researchers say the findings mean men have an alternative to drug therapy.

For around 50 years, women have been advised to perform pelvic floor exercises to strengthen their muscles for childbirth.

The pelvic floor is a “hammock” of muscles which support the bowel and bladder.

Pelvic floor, or Kegel, exercises involve clenching the muscles you would use to prevent yourself urinating.

This latest research indicates it is also important for men to maintain the muscle tone and function of their pelvic floor muscles with the exercises.

The team from the University of the West of England in Bristol studied 55 men with an average age of 59 who had experienced erectile dysfunction for at least six months.

The men, all patients at the Somerset Nuffield Hospital, Taunton, Somerset, were given five weekly sessions of pelvic floor exercises and assessed at three and six months, and asked to practise the exercises daily at home.

It was found 40% of the men regained normal erectile function – some of who had severe erectile dysfunction, and another 35% showed some improvement.

Two thirds of the men had said they also had problems with urination. These improved significantly after they began the exercises.

Dr Grace Dorey, a specialist continence physiotherapist who carried out the research, told BBC News Online: “The exercises were found to be equally as effective as taking Viagra.

“Pelvic floor exercises improve function in a physical way, in a more natural way.

“Men should be doing preventative exercise. It really is use it or lose it.”

She said men should be exercising their pelvic floor exercises from puberty onwards.

A spokesperson for the Impotence Association said: “The value and effectiveness of pelvic floor exercises should not be underestimated when considering the management of sexual problems such as impotence and premature ejaculation.

“The exercises are thought to strengthen the muscles that surround the penis and improve the blood supply in the pelvis, which is an important factor in relation to erectile dysfunction.”

http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/health/3036188.stm

The push-up is the ultimate barometer of fitness. It tests the whole body, engaging muscle groups in the arms, chest, abdomen, hips and legs. It requires the body to be taut like a plank with toes and palms on the floor. The act of lifting and lowering one’s entire weight is taxing even for the very fit.

“You are just using your own body and your body’s weight,” said Steven G. Estes, a physical education professor and dean of the college of professional studies at Missouri Western State University. “If you’re going to demonstrate any kind of physical strength and power, that’s the easiest, simplest, fastest way to do it.”

But many people simply can’t do push-ups. Health and fitness experts, including the American College of Sports Medicine, have urged more focus on upper-body fitness. The aerobics movement has emphasized cardiovascular fitness but has also shifted attention from strength training exercises.

Moreover, as the nation gains weight, arms are buckling under the extra load of our own bodies. And as budgets shrink, public schools often do not offer physical education classes — and the calisthenics that were once a childhood staple.

In a 2001 study, researchers at East Carolina University administered push-up tests to about 70 students ages 10 to 13. Almost half the boys and three-quarters of the girls didn’t pass.

Push-ups are important for older people, too. The ability to do them more than once and with proper form is an important indicator of the capacity to withstand the rigors of aging.

Researchers who study the biomechanics of aging, for instance, note that push-ups can provide the strength and muscle memory to reach out and break a fall. When people fall forward, they typically reach out to catch themselves, ending in a move that mimics the push-up. The hands hit the ground, the wrists and arms absorb much of the impact, and the elbows bend slightly to reduce the force.

In studies of falling, researchers have shown that the wrist alone is subjected to an impact force equal to about one body weight, says James Ashton-Miller, director of the biomechanics research laboratory at the University of Michigan.

“What so many people really need to do is develop enough strength so they can break a fall safely without hitting their head on the ground,” Dr. Ashton-Miller said. “If you can’t do a single push-up, it’s going to be difficult to resist that kind of loading on your wrists in a fall.” And people who can’t do a push-up may not be able to help themselves up if they do fall. “To get up, you’ve got to have upper-body strength,” said Peter M. McGinnis, professor of kinesiology at State University of New York College at Cortland who consults on pole-vaulting biomechanics for U.S.A. Track and Field, the national governing body for track.

Natural aging causes nerves to die off and muscles to weaken. People lose as much as 30 percent of their strength between 20 and 70. But regular exercise enlarges muscle fibers and can stave off the decline by increasing the strength of the muscle you have left.

Women are at a particular disadvantage because they start off with about 20 percent less muscle than men. Many women bend their knees to lower the amount of weight they must support. And while anybody can do a push-up, the exercise has typically been part of the male fitness culture. “It’s sort of a gender-specific symbol of vitality,” said R. Scott Kretchmar, a professor of exercise and sports science at Penn State. “I don’t see women saying: ‘I’m in good health. Watch me drop down and do some push-ups.’ ”

Based on national averages, a 40-year-old woman should be able to do 16 push-ups and a man the same age should be able to do 27. By the age of 60, those numbers drop to 17 for men and 6 for women. Those numbers are just slightly less than what is required of Army soldiers who are subjected to regular push-up tests.

If the floor-based push-up is too difficult, start by leaning against a countertop at a 45-degree angle and pressing up and down. Eventually move to stairs and then the floor.

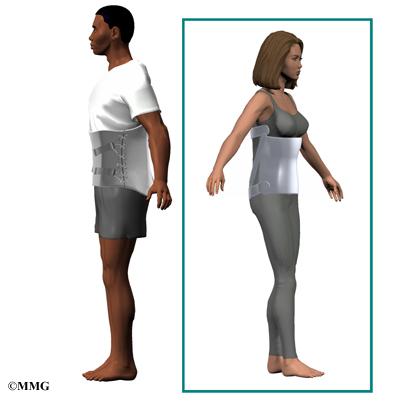

Lumbar or lower back supports — those large belts that people wear around their waists when they lift or carry heavy objects — are not very useful for preventing low back pain, according to a new systematic review.

Lumbar or lower back supports — those large belts that people wear around their waists when they lift or carry heavy objects — are not very useful for preventing low back pain, according to a new systematic review.

Although many people use lumbar supports to bolster the back muscles, they are no more effective than lifting education — or no treatment whatsoever — in preventing related pain or reducing disability in those who suffer from the condition, reviewers found.

“We recommend the general population and workers not wear lumbar supports to prevent low back pain or for the management of lower back pain,” said lead author Ingrid van Duijvenbode, a teacher and member of the research group at the Amsterdam School for Health Professionals in the Netherlands.

She and her colleagues looked at 15 studies — seven prevention and eight treatment studies — that included more than 15,000 people. When measuring pain prevention or reduction in number of sick days used, the researchers found little or no difference between people who used supports and their peers who did not.

“There is moderate evidence that lumbar supports do not prevent low back pain or sick leave more effectively than no intervention or education on lifting techniques in preventing long-term low back pain,” van Duijvenbode said. “There is conflicting evidence on the effectiveness of lumbar supports as treatment compared to no intervention or other interventions.”

The review appears in the latest issue of The Cochrane Library, a publication of The Cochrane Collaboration, an international organization that evaluates medical research. Systematic reviews draw evidence-based conclusions about medical practice after considering both the content and quality of existing medical trials on a topic.

“This continues the line of research that shows lumbar supports make no difference in treating or preventing low back pain,” said Joel Press, M.D., associate professor of physical medicine and rehabilitation at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine. “Looking at the literature on lumbar supports, it is difficult to make any conclusions because these studies are using supports for many different causes of low back pain. It would be hard to prove any one treatment is effective for every type of back pain, just as it would be difficult to prove that any one heart medication would be good for every type of heart problem.”

Press said that lumbar supports are useful only as an additional treatment to exercise and other interventions. He said that the bracing makes it more comfortable for some people to move around.

“I usually tell my patients asking about lumbar supports that while there is not a lot of evidence that it is useful overall, there are still individuals who might benefit from their use,” Press said. “But it should be used as an adjunct treatment if it helps to activate patients to increase their activity and exercise.”

Reference: van Duijvenbode ICD, et al. “Lumbar supports for prevention and treatment of low back pain (Review).” Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2008, Issue 2.

http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2008/04/080422202813.htm